In Venezuela, nothing is linear. Not even a Nobel Peace Prize. The 2025 award to María Corina Machado hasn’t improved the country’s reputation: it’s put it under a harsher microscope.

Far from producing a moral consensus, the award has opened a global plebiscite on the meaning of peace, the legitimacy of opposition leadership, and the political exploitation of prestige.

The tectonic plates that sustain Venezuela’s online reputation —chronic polarization, exile, sanctions, and allegations of human rights violations—haven’t shifted an inch; what has changed is the lighting on the stage.

From symbolic feat to permanent examination

The Norwegian Committee He justified the award by citing Machado’s contribution to defending democracy against an authoritarian regime, following his disqualification from office, and his unifying role in the 2024 electoral cycle.

Fact: The announcement is official and documented; the opposition leader becomes, de facto, an international figurehead for the Venezuelan democratic cause.

Up to this point, the story fits with the Nobel Prize tradition of rewarding dissent against closed regimes. But that very gesture triggers a relentless scrutiny: every phrase, every alliance, every precedent— including a letter sent in 2018 to Benjamin Netanyahu —becomes part of a real-time moral audit. The prize doesn’t shield: it exposes. And, in reputational crisis, exposure is synonymous with risk.

An award that legitimizes… and polarizes

The external narrative is clear: “democratic resistance,” “civic courage,” “human rights.” However, inside and outside Venezuela, different interpretations emerge.

Some highlight the symbolic value of the award as recognition of the struggle for free elections ; others are wary of Machado’s prior support for international sanctions and his affinity with controversial political figures, factors that—according to his critics—make the interpretation of the award more complicated.

The figure of Machado, awarded for her electoral drive and her defense of the civic path, coexists with the perception of a leader who relies on international pressure as a political tool. This duality is not new in the history of the Nobel Peace Prize: numerous laureates have embodied tensions between idealism and pragmatism, between moral symbolism and diplomatic strategy.

The 2025 case thus fits into that tradition of awards interpreted both as humanitarian gestures and as geopolitical messages.

Spanish silence and selective diplomacy

A symbolic fact weighed heavily on the public conversation: at the close of the first 72 hours after the announcement, the Spanish government had not officially congratulated Machado. However, prominent voices on the Spanish left openly criticized the award, reinforcing the perception that the prize functions as an ideological marker. The region replicated the usual logic: endorsements and silences speak volumes. In political marketing, what is not said also communicates.

The letter to Netanyahu and the archive as a trench

A few hours after the announcement, the 2018 letter resurfaced on social media and in the media, in which Machado asked for support from Benjamin Netanyahu and Mauricio Macri “to pave the way for freedom.”

The interpretation was immediate: for some, proof of strategic coherence; for others, confirmation of a policy that normalizes foreign interference.

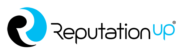

The episode was amplified when Colombian President Gustavo Petro reacted from his X account. recalling that letter and suggesting that the award to Machado had an obvious geopolitical dimension.

In his post—which has already surpassed several million views—Petro questioned the moral legitimacy of the award by mentioning the Venezuelan leader’s ties to Israel during the Gaza war.

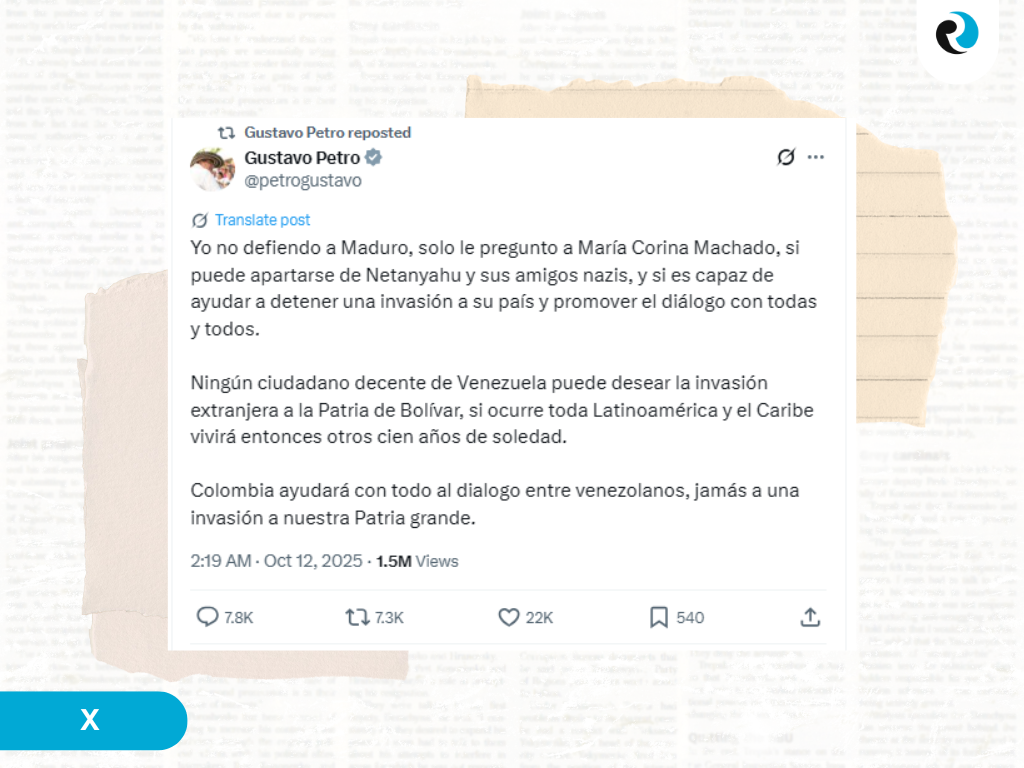

Shortly after, journalist Manuel H. Borbolla shared the original document, stating that the letter “exposes the true nature of the Venezuelan opposition and its international alliances.”

Both posts sparked a wave of comments that shifted the debate from the political to the reputational arena, reopening old wounds about the relationship between diplomacy, ideology, and legitimacy.

Beyond the content, the phenomenon illustrates a structural rule of the 21st century: the digital past never dies; it is republished. The archive has become a long-range artillery in online reputation wars : it reactivates frames, invalidates nuances, and crystallizes perceptions. The letter, whether authentic or manipulated in circulation, already operates as a symbol and, therefore, as potential reputational damage.

The Trump Angle: Between Gratitude and Capturing the Story

When the award was announced to María Corina Machado, Donald Trump didn’t hide his disappointment. In comments reported by Reuters and The Independent, the former president said he “should have won that Nobel” and claimed that Machado had called him to thank him for his support, telling him—in his own version—that he was accepting the prize “in her honor, because she really deserved it.” Smiling, he added: “I didn’t ask her to give it to me, although I think she could have. She was very kind.”

The backlash didn’t end there. As reported by The Guardian and later confirmed by Reuters, the White House accused the Norwegian Committee of having “put politics above peace” by awarding the recognition to Machado instead of Trump.

The episode reconfigured the international media narrative, shifting the focus from Caracas to Washington. What was supposed to be a celebration of Venezuelan activism became, for a few hours, a scene about the ego of a former president who, rather than losing an award, seemed to challenge the narrative of a moral victory. In the realm of political communication, the Nobel Prize ceased to be Venezuelan news and became just another chapter in the Trump universe.

Does this improve Venezuela’s reputation?

Not on its own. The Nobel Prize elevates a dissenting figure in the global narrative, but it doesn’t restore the country’s prestige.

reputation is a composite of indicators (governance, rule of law, press freedom, macroeconomic stability, legal certainty, human mobility) that cannot be altered by individual awards.

What the Nobel Prize does do is reorder the conversation: it forces governments, organizations, and media outlets to take a stand, and therefore, it re-exposes the Venezuelan divide.

In terms of the agenda, Venezuela is once again “on the front page”; in terms of trust, the country remains trapped between perceptions of negative exceptionalism and a political system with no prospect of verifiable reforms in the short term.

The boomerang effect: expectations and consistency

Every high-profile award generates expectations. For Machado, the bar will be consistency: maintaining a strategy that combines legitimate international pressure with domestic political construction, without letting the narrative of “peace and democracy” be swallowed up by hardball tactics.

Every contradiction will be amplified: an ambiguous statement, an unfortunate photo, an inconvenient ally. For the opposition, the challenge is not to turn the Nobel Prize into a paralyzing totem —or an alibi to renounce the path that the Committee rightly awarded: organization, electoral surveillance, operational unity.

For Chavismo, the communications task is to double down on the framework of attacked sovereignty and “moral colonialism” of the North; the apparatus already does this effectively.

For the real country, the prize doesn’t alleviate inflation, lower the cost of food supplies, bring medicines, or reverse the exodus. This gap between symbolic prestige and everyday life will continue to act as a reputational acid and a potential national reputation crisis if the narrative of peace becomes disconnected from concrete results.

The Latin American chessboard: peace, power and perceptions

Gustavo Petro ‘s criticism, centered on the letter to Netanyahu and the risks of an “armed provocation,” and the enthusiastic support from openly anti-Chavez governments and leaders, paint a predictable picture: global awards act as a proxy for alignments.

If this episode teaches us anything, it’s that Latin America lacks a common grammar for “peace” when it comes to sanctions, blockades, or military deterrence. For some, peace is built through verifiable elections; for others, it’s built through a resounding rejection of any coercive shortcuts. The Nobel Prize, in this sense, doesn’t arbitrate: it mirrors.

A lesson in method: how reputation is gained (and lost)

There are at least five rules that should be posted on the board:

- Awards don’t replace policies. International prestige accelerates headlines, not transitions. Without a domestic roadmap, every accolade evaporates into the noise.

- The archive doesn’t prescribe, but it does condition. The 2018 letter proves that digital footprints govern the present. Long-term consistency is a reputational investment—or a liability.

- Thanking is hard; who you thank is harder. Mentioning Trump strains bridges with sectors that could be persuaded. The prize demands adding, not encapsulating.

- Silence speaks volumes. The absence of a Spanish greeting at the beginning isn’t an oversight: it’s a diplomatic statement that weighs heavily on Europe.

- The Nobel Prize is a mirror, not a lifeline. It reflects who we are to the world; it doesn’t rescue us from what the world already sees.

What’s next?

For the opposition, it’s about professionalizing the coalition and strengthening procedures: civic audits, witness training, exhaustive documentation, strategic international litigation, and narrative discipline. For Machado, it’s about translating the symbol into method: less epics and more institutional pipelines ; fewer “credible threats” and more credible incentives to unblock the transition process.

For the international community, it’s important to move from applause to smart conditionality: technical and electoral support, phased incentives, measurable humanitarian openings, and explicit red lines against repression.

For Chavismo, understanding that the political economy of sanctions is no longer the only available narrative: social evidence demands a narrative—and policies—that don’t rely on external enemies to justify stagnation. All of this is part of a political marketing exercise that, whether well or poorly executed, will determine who wins the battle for global perception.

Conclusion: the mirror and the wound

The Nobel Prize awarded to María Corina Machado is, above all, an uncomfortable mirror: it reveals the desire of a part of the world to believe that Venezuela can still be rebuilt through the ballot box. But it also lays bare the wound: a fractured country, an opposition leadership subjected to the test of coherence, and an officialdom that has made survival its art.

In online reputation, symbols matter; in politics, they are not enough. If the prize doesn’t become a process—in verification, guarantees, organization, real politics—it will be just a framed postcard. And Venezuela doesn’t need more frames: it needs doors.