The attack on Miguel Uribe not only left a pre-candidate between life and death. It also reawakened the ghosts that Colombia had been trying to bury for years: political violence, polarization, institutional fragility. And with them, the question: To what extent has the country that sought to rebuild its online reputation with the world really changed?

One Saturday, an image that no one wanted to see again

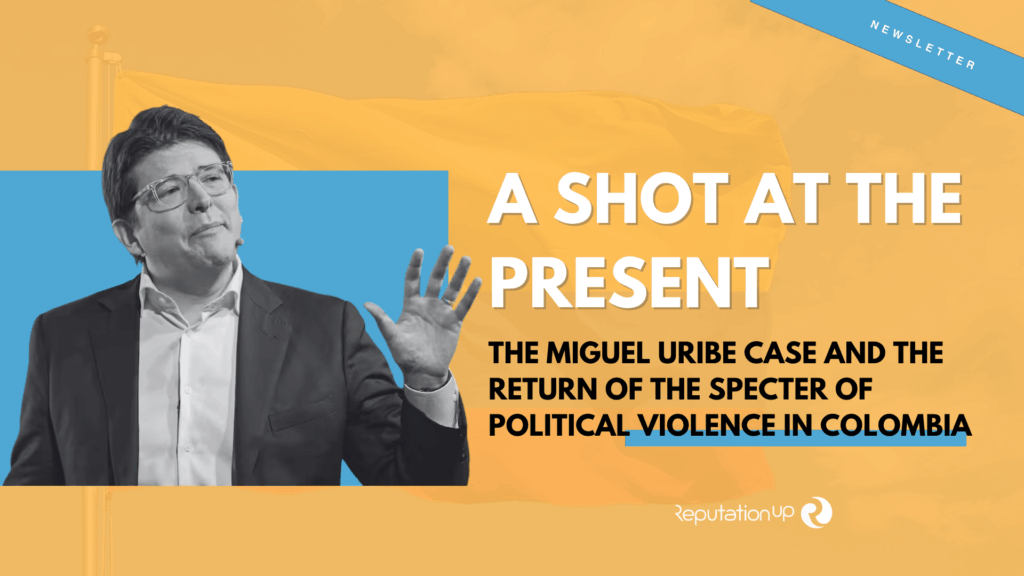

At 4:30 p.m. on Saturday, June 7, Miguel Uribe Turbay spoke to a small group of residents in a park in the Modelia neighborhood, in western Bogotá.

Without much logistical effort or armor, using an improvised platform made of beer crates and a wireless microphone, he explained his vision for improving mental health in Colombia, one of the issues that, according to him, should be at the center of public policy.

Minutes later, three gunshots interrupted his speech. One of them hit him directly in the head. Uribe, a senator from the Democratic Center and presidential candidate, fell to the ground before the astonished gaze of those around him.

He is 39 years old. Today, he is fighting for his life in intensive care at the Santa Fe Foundation. His prognosis, according to the statement published in X, remains “ very serious.”

The scene spread across social media and the media in a matter of minutes. This wasn’t just an attack on one person. What began as a neighborhood rally turned into a national tragedy that once again placed Colombia in the world’s spotlight for reasons it thought it had left behind.

An isolated case or an echo of the past?

For many Colombians, the images of the attack were all too familiar.

Luis Carlos Galán, Bernardo Jaramillo, Carlos Pizarro. All presidential candidates. All assassinated in the campaign. All symbols of a country where, for years, ideas were debated with bullets. During the 1990s, political violence was no exception. It was the norm.

Colombia has spent decades trying to distance itself from that image. The peace process with the FARC, the decline in kidnappings, the growth of tourism and investment, cinema, literature, urban innovation in Medellín and Bogotá. All were part of an effort to rebuild the reputational damage of a nation scarred by conflict.

And yet, in just a second, the country was back on the brink of collapse. Not only because of the severity of the attack, but because of what it represents: the possibility that, even today, politics can cost lives.

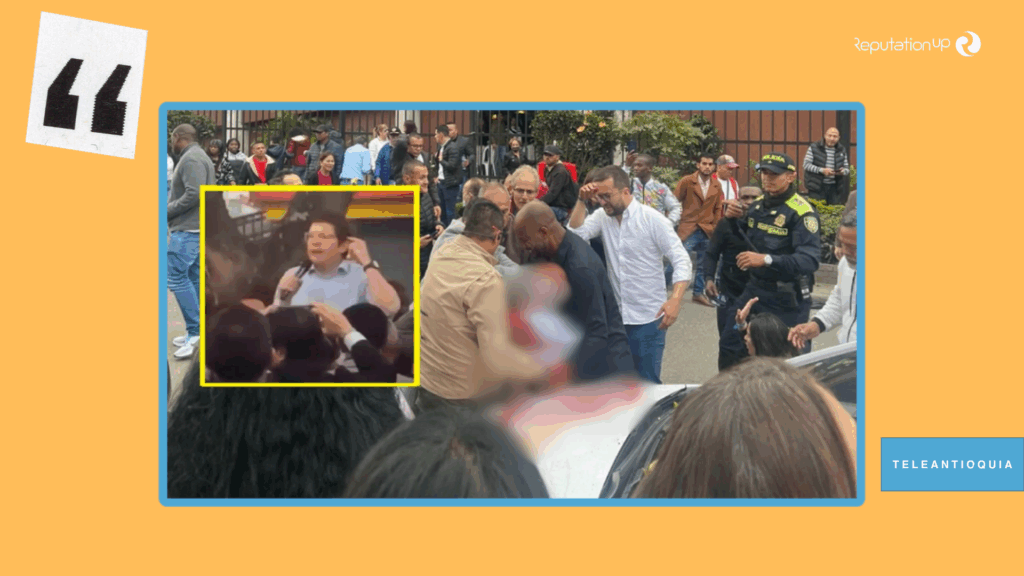

A surname steeped in history

The figure of Miguel Uribe Turbay cannot be understood without his personal history. The grandson of former President Julio César Turbay Ayala, he is also the son of journalist Diana Turbay, who was kidnapped by the Medellín cartel led by Pablo Escobar and killed in a rescue operation in 1991.

“I could have grown up with hate, but I chose forgiveness,” he once declared. At the age of five, he lost his mother to a gunshot wound. Thirty-four years later, he himself is on the brink of death from another gunshot wound.

The image has narrative force, but also political force. Uribe represents a generation that grew up among the ruins of violence and has attempted to enter the public debate in new ways. Its agenda is conservative, yet youthful. A critic of the current government, especially President Gustavo Petro, he had made institutional opposition one of his flagship projects.

And yet, this episode brings him back to the darkest legacy of national politics: violence as a tool, fear as a strategy, chaos as a language.

A country in shock… and divided

Reactions were swift. From the right to the left, all political parties condemned the attack. International organizations, public figures, and ordinary citizens did the same. The streets of Bogotá were filled with spontaneous marches with flags, candles, and messages of solidarity.

But beyond the initial unity, the attack also deepened existing fissures. Some voices pointed the finger at President Petro for his harsh rhetoric toward the opposition. Others rejected the insinuations and demanded that a tragedy not be politicized.

The president himself appeared hours later, after a security council meeting. He spoke of national unity, but diverted attention with disconcerting references: he mentioned Uribe’s Arab origins, spoke briefly in that language, alluded to “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” and criticized those he claimed were exploiting the incident, calling them “scoundrels.”

The ambiguity and disparity of his message was harshly criticized by various sectors, who considered it strayed from the central objective: the seriousness of the attack on a presidential candidate.

Bogotá Mayor Carlos Fernando Galán was more clear: he called for an end to “hate speech” and pointed out that the words of those in power can also trigger violence. His speech was applauded for its institutional tone.

Colombia’s reputation, another victim

For years, Colombia has invested resources and political capital in changing its image worldwide. It has promoted tourism, the orange economy, startups, gastronomy, and urban art.

It has signed peace agreements, hosted international summits, and championed a narrative of reinvention. All of that is shaken by news like this.

Images of a politician shot dead, videos of chaos in the park, the arrest of a minor as the alleged perpetrator… all fuel an external perception that Colombia has tried to eradicate: that of a country where violence still exists in the public sphere.

Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s Prime Minister, expressed her “solidarity with the Uribe family” and her “condemnation of this serious attack on democracy.” Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa also sent a message of support.

But beyond the diplomatic gestures, the reputational impact has already been felt. And it will be difficult to reverse if the next steps don’t match the gravity of the moment.

The figure of the minor hitman and the structural wound

The alleged attacker is 15 years old. He was arrested with a Glock pistol after being wounded by security officers. According to authorities, he claimed to have received a sum of money and requested access to his contacts’ numbers.

The Prosecutor’s Office has conducted raids on homes linked to his family and is continuing its investigation.

Beyond the specific incident, the case has brought a series of questions to the public agenda regarding the involvement of minors in violent acts, the associated vulnerability factors, and existing recruitment mechanisms.

Institutions, experts, and social organizations have highlighted the importance of strengthening prevention policies, access to opportunities, and child protection as part of a comprehensive response that helps mitigate these types of phenomena.

What’s at stake now?

Colombia is one year away from the presidential elections. The political landscape is expected to feature intense campaigns, complex debates, and a highly polarized environment. The recent attack has heightened the perception of institutional fragility and revived discussions about security levels during the electoral contest.

The government has announced measures to strengthen the protection of candidates. However, various sectors have argued that the challenge is not limited to physical measures, but also includes the need for a political environment that guarantees minimum conditions of democratic respect and stability.

Digital reputation could be influenced not only by the evolution of Miguel Uribe’s health, but also by the way in which the country manages the political context following the attack.

The institutional capacity to respond firmly, legally, and cohesively will be key to the country’s external and internal perception.

And the president?

Gustavo Petro came to power as the first leftist leader in Colombian history. With a career marked by his guerrilla past, his social activism, and his defiant rhetoric, he has sought to reshape the role of the state.

But leadership also demands restraint. The president has been criticized for excessively belligerent language, for accusing the opposition, and for speeches that strain the political fabric.

This attack presents him with an opportunity: to reaffirm his commitment to democracy beyond ideological differences.

Because if Colombia’s reputation is at stake, so is yours as head of state.

A before and after?

Miguel Uribe remains hospitalized. His family has asked for respect, silence, and prayer. Colombia, meanwhile, is confronting itself. Its history. Its present. The idea of what it wants—or doesn’t want—to be again.

This attack could be just another tragedy, diluted with the passage of time. Or it could be a real turning point. Not only to ensure electoral security, but also to redefine the political climate, the tone of debate, and the country’s perception in the eyes of the world.

Everything will depend on the decisions that are made. And those that aren’t.

Can Colombia preserve its democracy without losing its image?

It’s not just about protecting candidates. It’s about protecting the idea that politics is possible without violence. It’s about preserving a reputation that has taken years to recover. Ultimately, it’s about deciding which country you want to show the world: one that has learned from the past or one that repeats it.

🧠 What do you think?

Is this attack an isolated incident or a warning sign?

Is the government doing what it needs to protect democracy?

Can Colombia rebuild its image after this coup?

We read you in the comments.