When a national brand becomes an emotional symbol, any attempt at appropriation can trigger a legal crisis, a digital wave, and a reputational earthquake.

What really happened to Frisby?

On May 6, 2025, millions of Colombians were surprised by news on social media, newspaper headlines, and family chats: a company called Frisby España SL, registered in Bilbao, announced the opening of stores under the same name, logo, and aesthetics of the renowned Colombian fried chicken chain.

On its channels, the European company even referred to itself as “the legend of the chicken that crossed the ocean,” implying that this was an official expansion.

However, nothing could be further from the truth. The original company, Frisby SA BIC, with almost five decades of history in Colombia, reported unauthorized use of its name, logo, colors, and even its iconic mascot: Frisby the Chicken. It claimed to have no connection with operations in Europe and announced legal action.

The confusion was such that, for a moment, it was thought that Frisby had arrived in Spain to serve the more than 800,000 Colombian residents. What seemed like a positive announcement turned into an international controversy, with profound implications for the online reputation of both brands.

A name with history and an identity that cannot be improvised

Frisby wasn’t born in Europe. Its story began in 1977 in Pereira, Risaralda, when Alfredo Hoyos Mazuera and Liliana Restrepo decided to open a pizzeria that later became an icon of Colombian fried chicken. With more than 270 restaurants in 60 municipalities and 5,600 employees, Frisby is not just a company: it’s a symbol of national entrepreneurship.

That’s why the controversy ignited online. The Spanish company not only shared a name, but also a surprisingly similar visual identity. The logo, the warm colors, the friendly typography, and, above all, the endearing chicken mascot were practically identical. People didn’t need technical explanations: what they saw looked like plagiarism, and that was enough to light the fuse.

These types of conflicts show the need to apply tools such as reputational risk analysis before starting any international expansion process.

Plagiarism or legality? The “true use” loophole in Europe

From a legal perspective, the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO)determined that Frisby Colombia‘s European registration (filed in 2005) was invalid due to lack of genuine use in Europe. The law is clear: a registered trademark that is not used for five years can be revoked.

In December 2024, the Spanish company formally requested the cancellation of the Colombian registration, alleging exactly that. The EUIPO, after analyzing the case, provisionally granted the rights to Frisby España SL. Frisby Colombia now has two months to demonstrate that it has conducted real commercial activities with its trademark in Europe. Failure to do so will result in the loss of the registration and will be at the mercy of its European counterpart.

Here reputational component comes in : although the law protects Frisby Spain, international public opinion views with suspicion a company that adopts a brand that is almost identical to one that has deep emotional roots in another country.

This case is a textbook example of the need to integrate strategies for brand protection as an essential part of corporate identity.

New key elements have been added to this legal debate. Carlos Amaya, a lawyer specializing in trademark protection and partner at Amaya Intellectual Property, explained to Semana magazine that it was clear from the outset that this wasn’t a genuine expansion of Frisby Colombia, but rather an attempted takeover by a third party.

According to Amaya, “There is a website in Spain that could be misleading, falsely suggesting that Frisby has arrived in Europe. This constitutes misleading advertising and could be legally removed.”

The expert also emphasized that the “Frisby Chicken” character is not registered as a trademark in Europe by the Spanish company. However, the character is protected by copyright, which strengthens its legal protection.

“That design can be removed immediately, since it is protected by intellectual property, regardless of its trademark registration,” he stated. He compared the case to Disney characters, which enjoy global protection despite not being registered as trademarks in every country.

The price of chicken and the value of a brand

A 12-piece Frisby chicken combo costs around €21 in Colombia, the same product costs around €38 at KFC Spain. A hypothetical Frisby arrival in Spain could position itself with competitive prices, a familiar flavor, and an already established reputation. But that will only be possible if it manages to maintain its brand.

The case has also raised suspicions: some analysts suggest that Frisby Spain could be trying to profit by selling the brand to the Colombian original. A trademark squatting strategy that is increasingly common in international markets, and which is usually predictable with an active system of Google alerts.

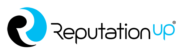

Home Burgers: the competitor that offered its kitchen

In an unexpected twist, the Colombian hamburger chain Home Burgers, with locations in Madrid, offered its facilities to Frisby Colombia so it could temporarily operate in Spain.

This alliance would allow Frisby to sell its products in an “in-and-out” format within established stores, meeting the effective use criteria required by the EU.

This gesture has been hailed as a rare and valuable example of corporate solidarity in times of crisis. Home Burgers’ reputation also stands to gain, as it prioritizes defending its Colombian heritage over its competitors.

All of Colombia raises its voice: patriotism, memes, and united brands

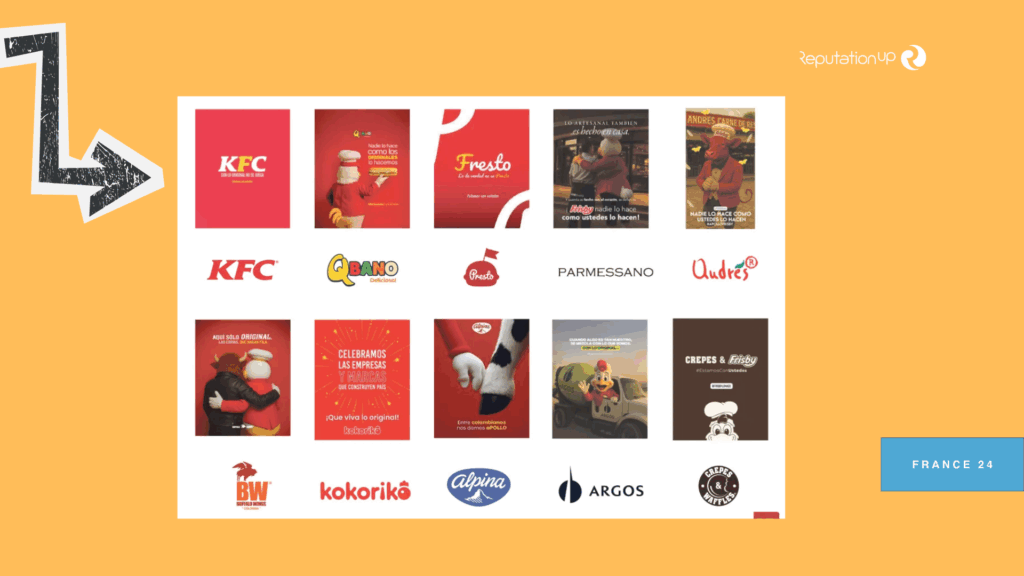

What came next was a rarely seen digital explosion. The hashtag #NosDamosaPollo went viral on X and Instagram. From rival chains like KFC and Kokoriko to companies in other sectors like Avianca, Alpina, Sura and TransMilenio, all aligned themselves with a narrative: Frisby is ours and is not to be touched.

Some memes depicted Chicken Frisby in a presidential ballot box; others presented him as a superhero protecting national gastronomic sovereignty. Humor, indignation, and national pride fused in a spontaneous campaign that is now studied by communications experts as an example of Political Campaign.

The political theme also took advantage of the moment. Journalist Vicky Dávila, a presumed Colombian presidential candidate, posed with the Frisby mascot in an image titled “For FRISBY’S VICTORY,” while former President Álvaro Uribe posted a montage with the slogan “Firm hand, big heart. And on his belly, the original Frisby.” All of this is a clear example of opportunistic political marketing that relies on the power of a beloved brand to generate sympathy.

The closure is not legal, it is reputational

Frisby Colombia isn’t just defending a brand name. It’s protecting its emotional legacy, its history as a brand, and its connection to the cultural identity of an entire country. The legal battle in Europe will determine whether it can maintain its registration, but the reputational trial is already underway— and it’s winning.

If this case proves anything, it is that the Digital reputation is not measured solely in stock market value, but also in emotional attachment. Brands that manage to become symbols, culture, and national pride have a defense that no notarized document can guarantee: people.

And what do you think?

Should a trademark lose its rights if it hasn’t used its registration, even if it’s decades old? Can a community save a brand with its collective voice? Are we facing a new paradigm where the law falls short of the power of reputation?

We read you in the comments.